As more and more FOSS projects leave the confines of dusty arcane mailing lists or thrice-cursed Bugzilla instances for the seemingly green pastures of the likes of GitHub or GitLab, there has been an ever greater need as a proactive user to engage and deal with these platforms. And, to be perfectly frank, the general experience sucks!

Their search interfaces especially leave a lot of things to be desired.

Usually I end up capitulating after a minute, clone the whole repository

instead, and fire up rg(1).

Why struggle to perform a task in your browser if you have tools that

have been perfected for it right in your terminal?

Another aspect GitHub has been working on is its review interface. From

my personal experience, patch reviews have been perfected on mailing

lists like git@vger.kernel.org, where people discuss proposed patches

by replying to them with in-line comments. After this review phase, an

improved version of the patch is sent in, and another review phase

begins, until there are no more points to discuss, and the patch is

either accepted or deferred.

It took GitHub a very long time to achieve relative feature-parity with patch reviews by mail. Now, the review interface exists and it works, but it is very crowded and needlessly convoluted. Finding old versions of a specific pull-request could be a lot nicer, as could be comparing subsequent versions to the original. Just about the best feature of having all this readily available in your browser is the ability to easily reference other bug reports, leading to improved inter-project communication. Of course a good mail archive frontend would solve this problem for mailing lists too.

Regarding repository landing pages, I feel that a Git web interface should show the state of the Git repository, not introduce me to a project. Chances are I’ve discovered a project’s repository through its website or project page, which hopefully already achieved the introductory part. Once I’ve found the repository, I’m ready to look at the code or browse a few commits; I don’t want to waste time reading a (possibly slightly different) project outline.

I want a system that augments my already existing CLI workflow in a practical way - something that enhances the experience in certain ways, and doesn’t completely recontextualize it. Which brings me to the present state… and a question.

The status quo

I have been hosting my Git repositories on my dedicated server for more than half a decade now, using a very simple (but effective) system:

- Initialize a bare Git repository in a well-known directory

- Tweak directory permissions (

0700if it’s private) - Enable the default

post-updatehook that runsgit-update-server-info(1) - Push my work to the server via

ssh(1)

Together with any old web server that can serve static files and a few

symbolic links in the right places, this setup enables most (if not all)

of what I need from a Git hosting platform. I can push and pull my work

using ssh(1), and the few public repositories I have are accessible

via pull-only HTTPS using Git’s “dumb protocol”.

I can even collaborate directly with other users on my server by

allowing specific people write access to the bare repositories. No git

user or group needed - just good old POSIX Access Control Lists. And for

people without a shell account on my server (the vast majority as it

turns out) there still was the possibility of using

git-send-email(1) to

contribute, of course1.

No web interface?

Over the last decade or so one thing has become very apparent: fully-featured and well-integrated collaborative platforms for development are there to stay, and users’ expectations have risen with them. Given these expectations, I’ve been asked more than a couple of times recently why I do not have a Git web interface for my projects. The answer’s always been the same, “why browse a repository with anything other than CLI tooling?”, but the question stuck with me…

It was trivial to find out why I didn’t set up a web interface initially, back when I set up the system I described above: I simply did not need one. This was a deliberate decision as I had recently migrated away from GitHub, which, back then, already contained most of the interactive web components it has now. My projects did not see a great deal of external activity, there were next to no bug reports, and most of the projects were too small to warrant integration into GitHub’s whole feature set. They were frequently starred2, but it did not seem that activity would pick up any time soon.

A web interface therefore was not even part of the equation.

Yes web interface!

These days, the question is harder to answer as I admittedly very much

recognize the ease of use and comfort of using a web interface to give a

project only a cursory glance, link a patch on IRC, or do a quick and

dirty blame on some broken code. As repository size decreases,

explorability on decent web interfaces increases, and, for the smallest

projects, a good web frontend can arguably fully replace git-clone(1).

So, do I need a web interface? No, not really. Do I want one? I think so. Given a decent enough candidate, I am confident that it will provide features other people find useful. Perhaps it will also boost visibility of what I am working on, and give me a nice stage on which to present projects still lacking their own post on this site. Plus, it is something to keep me occupied for a few days as I go about setting it up.

About I month back I set out to compile a full list of requirements:

- Self-hosted, without depending on popular containerized deployments

- A minimal and well-designed user interface

- No misguided social networking features (GitHub stars, I am looking at you)

- Active development, good documentation

- Easy integration with my preferred web server, Caddy

- Light on dependencies: no Ruby, no Perl, no PHP

- Not strictly necessary, but a bonus: no JavaScript

Searching for candidates

The search was on. I quickly found a very helpful list and started digging through it…

klaus

First up, klaus. The

demo looks promising enough,

except for the fact that one of the badges gets blocked by the

X-Frame-Options policy, but that is not relevant to the project

itself. It is built with Python, making hosting relatively easy with my

server setup, and also does not contain any features beyond simple

repository browsing.

My issues come with the overall design. I just… don’t like the way it looks. Lots of the core elements are very blocky, positioned too close together, and not contrasted enough. The diffs themselves look good, but the commit messages suffer from the same blocky and grey fate, drowning in the big wall of text below.

The design of the summary page feels strange to me as well, with most of

the page taken over by the rendered README file and no quick way to

see the last few commits other than scrolling all the way down. All of

this would need a great deal of work to fix, more than I am willing to

commit to right now.

sorcia

sorcia is a relatively new frontend written in Go. It’s still in alpha, and the “federation” part seems to be missing entirely, but is very pleasing to look at and use already. The homepage has the following to say:

Initially I’ve started building this project for myself as I’ve grown kinda frustrated with the noisy interface that I’ve been noticing on Github or other similar softwares. I started my career as a UI designer and then moved on to web programming, so I thought I could build and design something that would only have the necessary features which I need in order to host and develop my projects.

Sounds like what I am looking for. Sadly, a cursory look at the installation guide reveals a bit of a snag. For now, sorcia seems to use its own SSH server, and cannot be integrated to use an already running one. Bummer.

Additionally, without JavaScript, some things are not as nice yet as they could be. Picking this as a long-time solution right now is definitely a no-go. Maybe very well worth a look in year or so - if the project is still around by then. That said, I definitely appreciate the effort to create a nice user experience.

Addendum (2021-02-01): Indeed sorcia seems to be dead.

Gogs & Gitea

Now on to the big ones, the behemoths of self-hosted Git services: Gogs, and its more or less recent fork Gitea. I’ll focus on the latter only, seeing as the user experience is largely the same.

Gitea fulfills most of the requirements, with one huge caveat: The interface and features set is meant to match GitHub’s or GitLab’s. I will not only get a Git browser, but also an issue tracker, support for pull requests, a full-fledged wiki system, an activity tab, and the ability to watch repositories, star, and fork them.

Gitea’s not meant to have one instance per user, it’s meant to have one instance per company or community. And that community better be big! This puts me in a weird position where I am forced to go all in, but get nothing in return: If I were to consider enabling the issue tracker properly, I would also have to open up registrations; that means enabling authentication, allowing outbound mail, and fighting spam. All for the end result of people not wanting to register with yet another random instance on the internet.

On the other hand, if I disable3 all the features I do not need, the 10% that remains of the whole of Gitea is not even that great. Barely worth putting in the effort of going through its one thousand line sample configuration file.

cgit

cgit is probably one of the oldest web frontends for Git, next to gitweb (which comes bundled with Git itself.) As such, it is one of the most mature interfaces out there. Written entirely in C, the list of dependencies is expectedly short: cgit pulls in a tagged release of Git in the build stage, but other than that only depends4 on zlib.

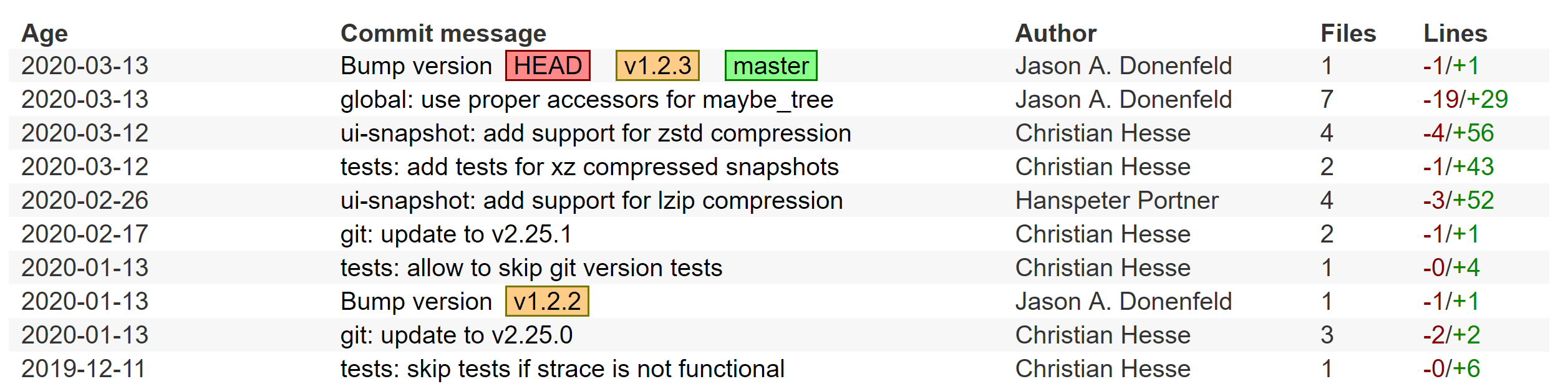

cgit is a Git web browser only, but has a bit of a different

approach compared to klaus and sorcia. While the latter two put more

emphasis on project presentation and present a fully-rendered README

file first and foremost, cgit focuses more on giving the user a

summarized view of their repository - showing a selection of the latest

active branches, tags, and commits.

In that regard, cgit might scare off users who are unfamiliar with git internals, but for me this is a welcome change. I can quickly scan through the summary view and find out what has been worked on recently, all without having to click through to another page. Of course cgit also supports markdown or manpage rendering, but it’s only a secondary concern.

All in all, I liked cgit the most and set out to deploy it. But things are never this easy…

Not-so Common Gateway Interface

There is an item on my list of requirements that calls for easy integration with Caddy, a web server I’ve been using for a couple of years now. Nowadays, most web applications actually run an HTTP server themselves and can easily be set up with Caddy acting as a reverse proxy. cgit, however, as the subtle name might reveal, runs via CGI, an ancient interface that relies on the web server executing the application for every incoming request.

This is a problem because Caddy does not natively support CGI. While there exists an abandoned plugin for Caddy 1, the recently released Caddy 2.0 does not share the same plugin interface and lacks CGI support completely. I deem it unlikely that it will ever get it.

Thankfully, both versions support FastCGI, an attempt to overcome the overhead of launching a process for every single request (most CGI applications are actually scripts run by interpreters, so this overhead can become quite noticable.) But how does one plug a CGI application into a FastCGI interface?

The answer is to use a FastCGI wrapper, a long-running process that acts as a bridge between the web server and the CGI application. Problem is that there are not many good ones around that are still maintained. All I could find after a few hours of search was a cursed Perl script, and an implementation in C that was more than 8 years old. Yikes.

slowcgi(8) to the rescue

A look on the OpenBSD side of things, though, revealed something very

promising: slowcgi(8). The

OpenBSD project is never really vocal about any of its programs, so this

slipped through the cracks easily - even though it’s been a part of the

operating system since version 5.4, released seven years ago.

slowcgi clocks in at around 1300 lines of C, is actively maintained, simple, secure by default5, and seemed very easy to port to Linux. In fact, it’s been ported already by someone else, but that version hasn’t seen any updates in about a year now - so I decided to roll my own thing (and will keep maintaining it for the time being). Instead of pulling in libbsd, I decided to just copy in the required parts of the OpenBSD source. In the future I might migrate over to using Kristap’s excellent oconfigure.

Once ported, slowcgi works right out of the box. By default it uses

a chroot to keep CGI applications jailed under a specific root

directory, and runs as a separate www user. A chroot for cgit is

technically not needed, but comes highly recommended. Even if it means

having to set up the entire chroot tree with cgit’s runtime

dependencies, defense in depth is important and makes the setup more

secure and safe in the long run.

Putting everything together

With slowcgi up and running, there’s only the matter of putting together all the pieces: Caddy needs to be set up to talk to the slowcgi instance controlling cgit, and the chroot needs to be set up properly. At this stage, considerations for backwards compatibility come into play also. Particularly, I did not want to have to move the already existing repositories to a new location. Everything that worked before should continue to work like before.

Since cgit will exist in a chroot, I cannot use symbolic links to any paths outside of it. Putting cgit into the same directory tree as the repositories seemed suboptimal also, as I want to keep the web interface and the actual Git data fully independent of each other for more flexibility in the future.

The general framework

I found my solution in a feature called “bind mounts”. People who have

needed to chroot(1) into a Linux installation from a Live CD might be

familiar with this - to give the installation access to devices mapped

by the host running from the CD, the whole /dev directory is bound

onto something like /mnt/dev. Thus, the same files are accessible

through multiple distinct mount points, with one of those contained

within the chroot.

This is the same concept I used in

skein(7), a small

framework facilitating a flexible and modular approach to multi-user

cgit hosting. Given a simple directory structure, a helper script sets

up all necessary devices6 and bind mounts for every user wanting to

give the cgit CGI application access to their repositories. If there is

a need to have multiple cgit hosts set up, this framework also allows

fine-grained control over which repositories show up on which host. This

way, users on my server who would like to opt in to having a cgit

frontend can freely determine how it is set up.

The following is part of the skein(7) framework, showing my home

directory in the cgit chroot. Symbolic links in each instance’s repos/

directory point to the actual Git repositories under the repos.avail

bind mount.

wolf

├── instances

│ └── git.oriole.systems

│ ├── config

│ ├── repos

│ │ ├── slowcgi.git@ -> ../../../repos.avail/slowcgi.git

│ │ └── [...]

│ └── site

│ ├── cgit.css

│ ├── custom.css

│ ├── favicon.svg

│ ├── logo.svg

│ └── robots.txt

└── repos.avail

As for cgit’s runtime dependencies… I’ve decided to keep these to an absolute minimum and use only statically compiled binaries to reduce the amount of work needed to maintain the chroot setup. Whilst this means that cgit will not have access to a shell (or, for that matter, a Python interpreter), a very decent chunk of its filter capabilities can still be used in conjunction with the wonderful lowdown and mandoc projects and a tiny custom C program invoking them.

Finally, the directives needed for Caddy are as simple as:

git.oriole.systems {

import shared

root /srv/cgit/home/wolf/instances/git.oriole.systems/site/

fastcgi / /run/slowcgi.cgit.sock {

env SCRIPT_FILENAME /bin/cgit

env CGIT_CONFIG /home/wolf/instances/git.oriole.systems/config

except /cgit.css /custom.css /logo.svg /favicon.svg /robots.txt

}

}

Configuring cgit

All that remains now is configuring cgit itself to work with this

framework. There’s not much to be done in that regard, it simply needs

to be pointed to my custom

cgit-about-filter

program, and the repository location within the chroot:

about-filter=/bin/cgit-about-filter

scan-path=/home/wolf/instances/git.oriole.systems/repos

For projects with a README file formatted in markdown, lowdown(1)

will take care of HTML conversion. Manuals are formatted by mandoc(1).

Given the lack of a Python interpreter there is no syntax highlighting,

but I find excessive syntax highlighting unappealing anyway. A couple

more changes to cgit’s default cgit.css… and we’re done!

git.oriole.systems

Finally, after about a week’s worth of research, experimentation, and setup work, my new Git web interface is finally online under git.oriole.systems! A great deal of care has gone into setting it up just right, and I dearly hope this will be useful for people, enjoyable to use, and interesting to just browse around in.

Future work

A few things remain to be done in the next few weeks and months. For

one, I’ll have to look at changing my Caddyfile to be compatible with

the recent release of Caddy 2, before I fully switch over to it. That

means having to relearn most of what Caddy does, and may be a bit

time-consuming. Of course I’ll also have to remain backwards compatible

with all the things I have already set up.

There’s a few things to be done on the Git web interface front, too:

Right now I still serve Git repositories using the “Dumb

HTTP”

protocol. Integration with Git’s own

git-http-backend(1) would

be a good addition. Furthermore, I have been planning for a very long

time to set up a public inbox for issue

tracking and bug reports. Once that is set up, I’ll have to link to the

proper addresses from within each Git repository.

All this will be part of a future post. For now, enjoy.

-

The chances of that happening are tremendously low, but hope dies last, as they say. ↩

-

To my eternal chagrin, the project with the highest amount of stars was a hastily thrown-together shell script that fired up a now-playing notification for mpd… ↩

-

Not even supported yet, but is introduced with the upcoming

1.12.0. ↩ -

The README mentions libcrypto and libssl, but as far as I can tell these are not needed. Git switched to its own SHA1 implementation a few years back, and libssl may only be required for

git-imap-send(1). ↩ -

Sadly there’s no good way to do

pledge(2)nicely on Linux, so those parts are ignored. And no, I’m not going to pivot toseccomp(2). ↩ -

For now that is just /dev/null. ↩